Moonshine. White lightning. Mountain dew. They’re all names for that distilled spirit made of grain and a dash of illegal activity. Back in the mid-1900s, you might just as well call its maker — the bootlegger — the mascot of the “Dark Corner” in the Carolinas. But moonshine got its start much earlier than that.

The Beginnings of Distillation

Like most New World histories, the history of moonshine begins farther back and in a land across the ocean.

Distillation itself may have first appeared during the 3000s B.C. in Mesopotamia or Egypt. Those early Middle Easterners likely used stills to create their own customized perfumes.

Inhabitants of Asia also used distillation to extract scents from plants, as early as or even earlier than the Middle Easterners.

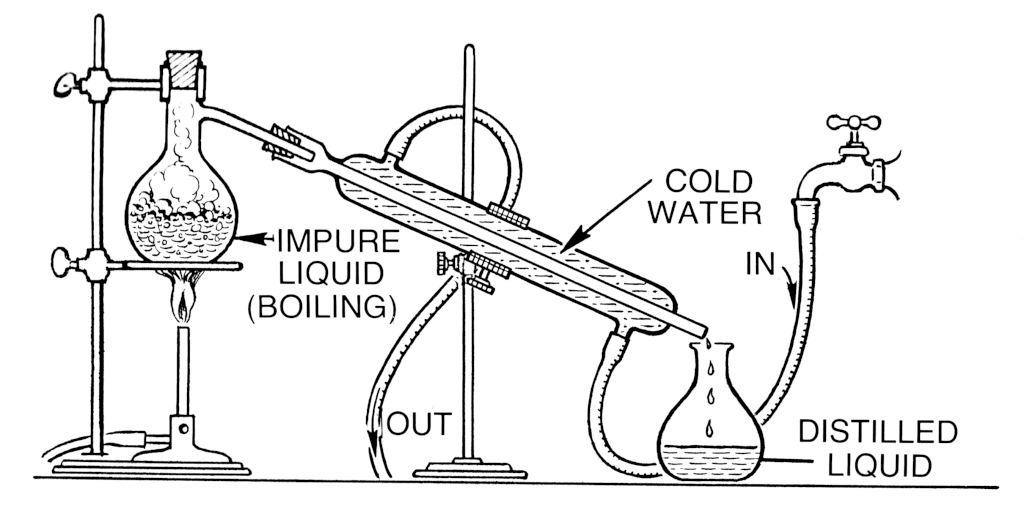

So how exactly does distillation work? The process of distillation purifies a liquid mixture by heating it up and collecting its vapor as it cools back down. The non-volatile components (those that don’t readily evaporate) remain in the original mixture, while a purer, more concentrated liquid emerges in a separate container.

From its discovery onward, these early societies used distillation for a number of purposes, such as to create medicines, dyes, and essences.

“Water of Life” Comes to Life

But not until the 12th century A.D. did anyone think to distill alcohol. During this time, the Italians began putting wine into stills to create a harder spirit or brandy, which is a general term used for any fruit distilled in alcohol.

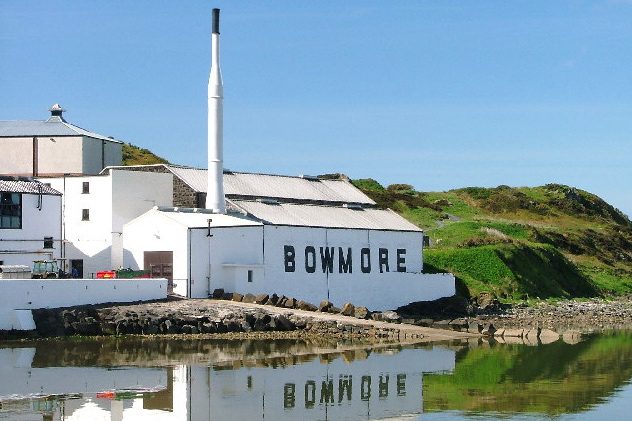

Two hundred years later, alcohol distilling had reached the shores of nearby European neighbors in Scotland and Ireland. It was they who first invented whiskey, or in Gaelic usquebaugh — a word meaning “water of life.”

To be certain, they realized the medicinal benefits of the strong drink early on.

As the BBC defines, the whiskey-making process goes something like this:

1. Crush the grains (barley, corn, rye, wheat, etc.) to create the grist.

2. Add water to the grist to form the mash.

3. Boil this mixture, and then allow it to cool.

4. Add yeast, which carries out fermentation by eating the sugars and yielding alcohol.

5. Drain the resulting liquid, which is now beer.

6. Distill the beer using a still.

7. Age the resulting liquor in wooden barrels.

Unlike the Italians, who used a fruit base for their wine, the United Kingdom made their beverage of choice with a grain base of barley. Both the base, alcohol content, length of aging, and storage method set whiskey apart from other spirits.

Eventually, United Kingdom authorities realized the financial advantage to be gained by implementing taxes on these distilled liquors.

“Up to 1556 the distillation of spirits was carried on in Ireland without license or taxation,” says T. Fairley in “The Early History of Distillation.” “The attempts to raise revenue by granting monopolies or licenses, and, later, by taxation on the liquids produced, were long opposed and resented by the people, and the illegal manufacture often exceeded the amounts on which taxes were paid.”

And so it was that bootlegging was born.

Whiskey in the New World

To escape the high level of taxes in their motherland was, in part, one of the reasons the pilgrims decided to steal away to the New World, where they hoped to establish a less restrictive government.

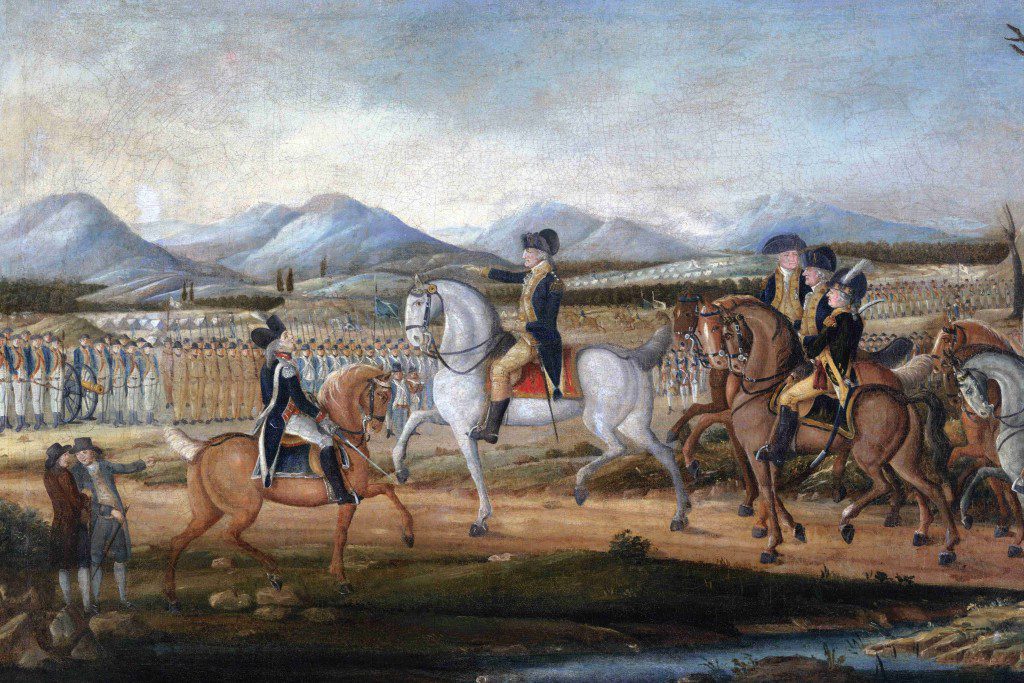

Unfortunately for distillers who’d made their way over, the new government also caught on to the idea of taxing distilled spirits to help pay off its debt. In fact, the Excise Whiskey Tax was the very first tax imposed on a domestic product under America’s newly formed federal government.

Unrest over this tax surmounted in the 1794 Whiskey Rebellion, in which several thousand unhappy farmers and their allies violently protested the tax in Pennsylvania and made talk of separating from the U.S. President George Washington responded by sending over 10,000 troops across the state to settle down and disperse the rebel groups.

Under Thomas Jefferson’s presidency, Congress did away with the excise tax on alcohol, but the tax came and went several more times between the early 1800s and 1930s.

The Temptation of Bootlegging

The 1920s — known as the Prohibition Era — was the darkest point in history for distillers in the U.S., when the 18th Amendment banned the production, transportation, and distribution of intoxicating liquors of any kind.

During this era, another began: the Great Depression. And no area was poorer in the U.S. than that of Appalachia, touching the Southeastern states and, perhaps most notoriously, the “Dark Corner” of the Carolinas.

In this area — largely defined by an agricultural lifestyle — farmers struggled to make ends meet. They often gave in to the risky temptation of bootlegging, if for no other reason than that illegally produced whiskey garnered more profit than corn plain and simple (which they used as their whiskey base, rather than barley).

For example, a farmer might sell five bushels of corn at market for $.50 each, says Dark Corner historian Dean Stuart Campbell. This would earn the farmer a gross income of $2.50 for his five bushels of corn.

However, if that same farmer turned his five bushels of corn into 12 or so gallons of moonshine — corn whiskey made under the shine of the moon, so as to avoid being caught by the authorities — then he could sell each gallon for $1 and make a total of $12.50 from the same amount of corn.

Due to its high value, moonshine was as good as money in those days, and a large population of the Dark Corner wanted their piece of the pie, or at least their swig from the bottle. Area residents continued to drink it often, both recreationally and for medicinal purposes.

From the 1930s up through the ‘50s — even after Prohibition had been lifted — moonshining was so common that you could spot a still on every creek and stream in the mostly wooded northern part of Greenville County.

Still Distilling Today

Today, distillers don’t have to be as secretive as they once did. Making spirits is both legal — provided you have a license and pay your taxes — and popular, with a surge of distilleries popping up across the U.S. in recent years.

And the Upstate of South Carolina has been no exception, ever since legislation introduced in 2009 made allowance for the operation of microbreweries in the state. Dark Corner Distillery, Six & Twenty, Rock Bottom Distillers, and Palmetto Distillery all call the Upstate home.

As does Copperhead Mountain Distillery in Travelers Rest, where native John Connelly and his family make small batches of fine whiskey — from the aptly named 100-proof Snakebite to the more delicate, fruity Passionate Peach — just like their ancestors did, only better.

“This is like an art form to me,” says Connelly. “All I need to do is keep practicing my art till the day I die.”

Connelly also gives regular tours of the distillery, which include a peek behind the scenes, samples of their products, and a rundown of whiskey history on up to the present.

“I’ve literally found 35 to 40 busted up still sites. There are 100s to 1000s untouched. To this day, they’re sitting and rotting,” says Connelly, who’s often hiked up through Dark Corner mountains in search of such sites. “They’ll be there another couple hundred years.”

And so will, we imagine, the craft of distilling.

[Note: Our blogger Celeste was invited to Copperhead Mountain Distillery as a member of the media, where she received a free distillery tour. The tour served as a starting point for much of the information in this post. For that, she would like to express thanks to the Connelly family. She did not receive payment to write this content. All opinions are her own.]

[jetpack-related-posts]

Sources:

“A Guide to the Lingo and History of Whiskey” by Suemedha Sood / BBC.com

Copperhead Mountain Distillery tour with John Connelly

Eyes to the Hills by Dean Stuart Campbell

“Prohibition” by History.com

“The Early History of Distillation” by T. Fairley

“The Whiskey Rebellion” by Dave Alexander / LegendsofAmerica.com

“The Whiskey Rebellion” by PBS.org

“Upstate Distilleries Are Crafting Some Mighty Fine Hooch” by Sherry Jackson / OurUpstateSC.Info

Photo Credits: Featured/Moonshiner John Bowman — Public domain; Perfume maker — Rudolf Ernst / Public domain in those countries with a copyright term of life of the author plus 80 years or less; Distillation diagram — Public domain; Bowmore Distillery — Mick Garatt; Whiskey Rebellion — Public domain because its copyright has expired; Dumping liquor — Orange County Archives; and John Connelly — Celeste Hawkins